On Feb. 1, the Ukrainian World Congress (UWC) hosted a webinar titled “The Long-Term Impact of Russia’s Abduction of Ukrainian Children” as part of the global campaign “Stand With Ukraine: Protect Future Generations,” marking the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

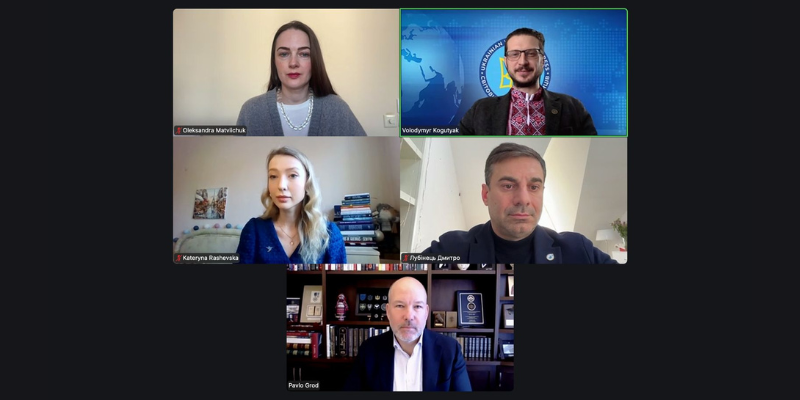

The event brought together international experts, human rights advocates, and representatives of the Ukrainian diaspora to examine the humanitarian, legal, and psychological consequences of the deportation of Ukrainian children, as well as advocacy tools to support their return.

A systemic crime against the Ukrainian nation

UWC President Paul Grod stressed that Russia’s abduction of Ukrainian children is a deliberate state policy planned at the highest level.

“This is not only about thousands of children taken today — it is an attack on the future of the Ukrainian nation, its demographics, identity, language, and historical memory,” he said.

According to Grod, the crime must be viewed in the long term, and the international community must respond clearly and consistently to prevent its lasting consequences.

The webinar was moderated by Volodymyr Kogutyak, UWC Vice President and Head of Advocacy, who emphasized the importance of turning emotional solidarity into concrete action that can influence political decisions and the legal classification of these crimes.

Children as targets of a genocidal policy

Oleksandra Matviichuk, Chair of the Center for Civil Liberties and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, explained that the abduction of children is only one component of Russia’s broader genocidal policy. In occupied territories, Ukrainian identity is systematically erased, the Ukrainian language and culture are banned, and men are forcibly conscripted into the Russian army.

“Children are sent to Russian ‘re-education’ camps and raised as Russian citizens,” she said.

The issue extends beyond children who have been physically deported. More than 1.6 million children remain in occupied territories, where they undergo what Matviichuk described as “a thorough erasure of identity.” They are taught using Russian textbooks, enrolled in militarized youth programs, and issued Russian passports.

“This is not only a human rights issue but also a security threat,” she warned. “Children stripped of their identity may be recruited into the Russian army once they turn 18.”

Matviichuk emphasized that the stories of Ukrainian children living under occupation or in deportation are a crucial part of the truth about the war. Despite pressure and forced Russification, children continue to find ways to preserve their Ukrainian identity — from underground book clubs to open, though dangerous, acts of resistance.

“These examples show not only the scale of Russia’s crimes, but also the strength of those in the most vulnerable position,” she said, noting that such stories leave adults with no room for indifference or despair.

“When children in occupied territories create underground book clubs, refuse to sing an imposed anthem, and find the strength to resist, it speaks not only to Russia’s crimes but asks all of us a simple question: if they can do it, what right do we have to give up?”

State policy, international mechanisms

Dmytro Lubinets, Ukraine’s Parliamentary Commissioner for Human Rights, outlined the stages of Russia’s policy toward Ukrainian children. Since 2014, Russia has systematically carried out deportations, document changes, and identity manipulation.

He cited key figures: Russian occupation authorities claim that more than 700,000 children are currently in Russia; 1.6 million children lived in occupied Ukrainian territories; approximately 20,000 Ukrainian children have been forcibly transferred or deported; and as of today, 1,975 children have been returned to Ukraine through the Bring Kids Back UA initiative.

Lubinets stressed the importance of the international coalition supporting the return of Ukrainian children and the need to recognize Russia’s actions as war crimes and acts of genocide. He also called for sustained international awareness and stronger support from partner states.

International humanitarian, criminal law

Kateryna Rashevska, an expert in international humanitarian and criminal law, emphasized that international law still has the power to protect children — if it is applied effectively.

She reminded the audience that the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide explicitly prohibits the forcible transfer of children from one ethnic group to another. Russia, however, attempts to justify its actions by its own interpretation of children’s rights and “best interests,” violating international norms and restricting the rights of Ukrainian children.

Rashevska stressed that the key priorities are ensuring legal accountability without exception, rejecting any form of amnesty, and incorporating the issue of abducted children into all international agreements related to the war.

Terms to use:

- Unlawful deportation — the forced transfer of a person across national borders, for example, from Ukraine to Russia or Belarus.

- Forcible transfer — the forced relocation of a person within a single state, for example, from Mariupol to Donetsk or from Kherson to occupied Crimea.

Both concepts constitute serious violations of international humanitarian law and fall under the provisions of the Rome Statute. A central element of these crimes is indoctrination—deliberate attempts to re-educate and mentally reshape children.

Terms to avoid:

- Trafficking in persons — using this term broadly to describe cases of abducted Ukrainian children can create legal confusion and blur distinctions between different categories of victims.

- Kidnapping — this term should also be avoided because it does not capture the specific nature of mass crimes against children in the context of war and genocide.

Rashevska emphasized that only definitions enshrined in international treaties and consistently applied in international jurisprudence should be used to correctly classify Russia’s crimes.

Turning solidarity into sustained pressure

During the second part of the webinar, speakers discussed how Ukrainian communities and international organizations can maintain global attention on the issue of abducted children. Matviichuk urged communities to offer clear, actionable steps in every country and to present children’s stories not only as stories of victimhood but also of resistance. Underground book clubs in occupied territories, she said, are powerful symbols of cultural survival and defiance.

A call to action

The abduction of Ukrainian children is a systematic, premeditated crime with genocidal intent, carrying long-term humanitarian, psychological, and security consequences. Speakers emphasized the need for sustained international pressure on Russia, the return of abducted children, accountability for perpetrators, and continued support for Ukrainian communities worldwide.

The UWC calls on global Ukrainian communities and international partners to take a firm, uncompromising stance. The priority is to document the aggressor’s crimes, expose the truth, and demand the return of abducted children through international courts. There can be no concessions and no “business as usual” with a state that commits such crimes.