On October 1, 2022, Ukrainians in Croatia celebrate special jubilees: the 100th anniversary of the Ukrainian Society “Prosvita” the 50th anniversary of the Cultural and Educational Society of Ruthenians-Ukrainians “Kobzar.”

With much respect to these Ukrainian organizations, here is a brief account of the fascinating history of the first settlers on Croatian lands and of the storms that the Ukrainian and Croatian peoples have been enduring.

The first settlements

The ties between Ukraine and Croatia are much stronger and longer than it might seem at first glance. For example, we can say that the first people who migrated from the territory of modern Ukraine to the territory of modern Croatia were… Croats! More precisely, white Croats who migrated as long ago as the first millennium AD. As many scientists assume, the lands of White (Great) Croatia extended, in particular, to a part of western Ukraine, and even the capital of the White Croats is said to be the settlement that existed near the current village of Stilsko in Lviv Oblast. What is more, there is a hypothesis that the name of Khoryv, one of Kyiv’ legendary founders, comes from the word “Croat.” Therefore, the subsequent migration of Ukrainians closer to the gentle Adriatic Sea can be considered as simply following the example of the Croats themselves.

Before the First World War

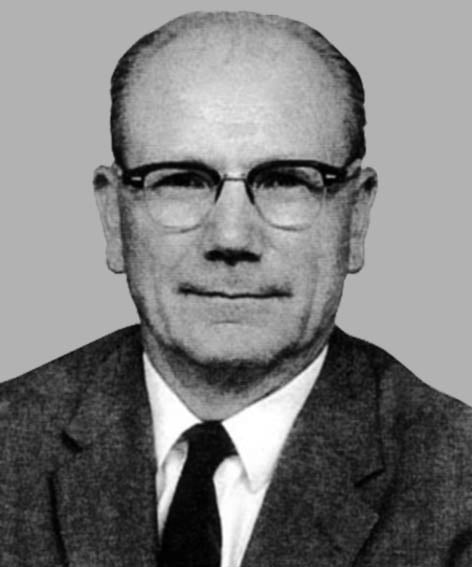

Julije Drohobeczky, church figure, teacher and conductor. In December 1891, he was appointed Bishop of Križevci for Greek Catholic Ruthenians in Croatia. He built the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Križevci and the Church of the Annunciation in Pribić. He founded 9 new parishes, built a boarding school for boys at the diocese, opened a Basilian monastery. He headed the Croatian Music Institute and the Red Cross in Križevci

Julije Drohobeczky, church figure, teacher and conductor. In December 1891, he was appointed Bishop of Križevci for Greek Catholic Ruthenians in Croatia. He built the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Križevci and the Church of the Annunciation in Pribić. He founded 9 new parishes, built a boarding school for boys at the diocese, opened a Basilian monastery. He headed the Croatian Music Institute and the Red Cross in KriževciHowever, when it comes to the history of Ukrainians in Croatia, its beginning is generally assumed to be the year 1745, when the first Ukrainian-Ruthenian settlements appeared in Bačka – a geographical and historical area that partially covers the territories of modern Serbia and Hungary. Regarding the territory of modern Croatia, then the first Ukrainians, namely Transcarpathian Ruthenians from Bačka, settled here 122 years ago – on the border with Bosnia.

Why “Ruthenians”? At that time, Transcarpathia was still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, so the endonym “Ukrainian” was not common among the inhabitants of the region; most Transcarpathians called themselves Ruthenians.

The life of Ukrainians who settled on the Croatian lands more than a hundred years ago was not at all similar to the vacationing of present-day Ukrainian tourists in the resorts of Dalmatia. According to Olena Malynovska, chief researcher of the National Institute of Strategic Studies, Ruthenians-Ukrainians here were mainly engaged in agriculture. “Compared to the local population, they possessed more advanced methods of cultivating the land. They were first to introduce iron plows here and demonstrated the advantages of deep plowing.” The local population took over from them the custom of plastering and whitewashing buildings as well as using beds and kitchen stoves in everyday life.

Despite the difficulties, the migrants very quickly created their own institutions, primarily religious centers – churches and parishes. Presence of Ukrainian cultural centers allowed for easier integration into the local society and for preservation of national characteristics, such as language and culture.

The interwar period and the Second World War

The late 19th and early 20th centuries feature the second wave of Ukrainian emigration to Croatia followed by the third wave in the wake of WWI. It included not only peasants, but also officials and scientists, doctors and writers, engineers and artists, priests and soldiers, as well as statesmen of the Ukrainian People’s Republic and of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic. At that time, the Ukrainian and Ruthenian population within the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes totaled about 50,000. Young people from Halychyna came to study in Zagreb.

Vasyl Voytanivsky, Prosvita society head (left), and Yosyp Koropey, one of the most active members of the OUN in Croatia – photo from the book “Before the march to the east” by Z. Knysh

Vasyl Voytanivsky, Prosvita society head (left), and Yosyp Koropey, one of the most active members of the OUN in Croatia – photo from the book “Before the march to the east” by Z. KnyshThe desire for win and to strengthen their independent states united the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) with the Croatian nationalist movement Ustaše. OUN leader Andriy Melnyk and Ustaše leader Ante Pavelić were considered to be friends.

It was during the interwar period that the first Ukrainian organizations appeared in Croatia. In 1922, the Ukrainian society “Prosvita” was founded in Zagreb. Ivan Budz was elected its first chairman of the Board and later became its Honorary Chairman, while the Prosvita’s chairmanship was taken over by the legendary Vasyl Voytanivsky (Vasilj Vojtanivskij).

Born in Galicia (Halychyna), 28-year-old Vasyl Voytanivsky moved to Zagreb, where he studied, served in the military and became the head of the OUN in Yugoslavia. In 10 years, Vasyl married Vlatka Rožman, a Croatian. His wife and two children spoke fluent Ukrainian.

In 1941, the Independent State of Croatia was proclaimed on the territory of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina with Ante Pavelić as its poglavnik (leader). It was Voytanivsky who radioed greetings to the state independence of Croatia on behalf of Ukrainians. In 1941-1945, he led the Ukrainian Representation in the Independent State of Croatia and became one of the founders of the Ukrainian Legion in Croatia.

The Ukrainian Legion was considered part of the Croatian army – the National Guard. Its soldiers wore Croatian military uniforms, and the Ukrainian volunteers had blue-and-yellow armbands and stripes in the form of a white shield with a black trident. It was assumed that the Legion would be sent to the Eastern Front to fight the Red Army in the territory of Ukraine. However, Voytanivsky’s hopes did not come true, and the Legion was sent to Bosnia. In 1945, Yugoslav red partisans arrested Vasyl Voytanivsky and shot him to death. His wife and son were also executed.

Antin Ivakhniuk (Iwachniuk, pseudo – Vuyko) was another one of the most prominent Ukrainian cultural figures in Croatia. A public man and philanthropist, a member of Plast and Prosvita, a schoolmate of Roman Shukhevych, with whom he was part of the underground movement. After imprisonment in Poland for involvement in a secret circle, in 1933, Antin left for Zagreb, where he founded the Ukrainian student society “Probojem” (later – “Dnipro”). He actively participated in public life in Croatia, wrote articles, interviews and reviews. Three years after he was arrested by the NKVD in Zagreb, he emigrated to Canada.

Yakiv (Jacques) Hnizdovsky, Ukrainian-American painter, printmaker, graphic designer, illustrator and sculptor. In 1939–1944, he lived in Croatia and studied at the Zagreb Academy of Arts

Post-war period

The 1950s became the period of Yugoslav Ukrainians’ most intense migration, with 5,000 leaving the country and thousands more migrating within its borders. As of 1961, there were 6,290 Ruthenians and Ukrainians left.

In May 1972, the Cultural and Educational Society of Ruthenians-Ukrainians was founded, renamed in 2012 as the Ukrainian Cultural and Educational Society “Kobzar” Zagreb. Over its 50 years, the society has been led by Markijan Ružickiy, Vladimir Krajcar and currently Slavko Burda. The society supports the preservation of cultural heritage and actively engages in book publishing.

Slavko Burda, Ukrainian public figure in Croatia. Graduated from Zagreb University. An active participant in and organizer of the cultural and educational life of the Ukrainian diaspora. From 1983 – a secretary of the cultural and educational society of the Zagreb Union of Ruthenians-Ukrainians, from 1992 – the chairman of the Zagreb Society of Ruthenians-Ukrainians in Croatia and a member of the board of the Union of Ruthenians-Ukrainians in Croatia, from 1995 – a secretary of the Croatian-Ukrainian Society, from 1997 – the chairman of the Ukrainian Cultural and Educational Society “Kobzar” Zagreb. In 2022, “Kobzar” began publishing its Slovo Kobzarya quarterly, and Slavko Burda is its comiiler. He was a member of the editorial board of the Nova Dumka magazine. One of the organizers and the director of the annual summer school of language and culture of Ruthenians and Ukrainians in Croatia. An organizer of cultural and educational events of the Union of Ruthenians-Ukrainians in Croatia, international conferences and exhibitions, dedicated to the culture of Ukraine and of the diaspora and the author of publications about the diaspora

Mutual recognition and independence

Croatia was among the first countries to recognize Ukraine’s independence. In return, Ukraine became one of the first UN member states to recognize Croatia’s independence.

However, Croatia’s 1991–1995 War of Independence against the aggression of the united Greater-Serbian forces broke the peace once again. Ukrainians found themselves at the epicenter of the fighting, as hostilities engulfed the territory, where 80 percent of the Ukrainian diaspora lived.

In Vukovar alone, during the 86 days of the siege, 132 Ruthenians-Ukrainians were killed and 270 wounded, more than 300 were imprisoned in Serbian concentration camps, 500 were expelled from their native places, and another 100 fled from persecution. Their total relative losses during this war amounted to 3.5% – even more than during WWII (2%); exiles and refugees made up half of the Ukrainian diaspora.

The Serbian aggression interrupted studies in several schools where Ukrainian and Ruthenian languages were taught. Many teachers were killed, expelled or went missing. School stocks of books and premises were destroyed or looted.

Such hostile attitude of Serbs towards Ukrainians and Ruthenians could be explained by the fact that representatives of the Ukrainian diaspora took an active part in the defense of Croatian independence and its territorial integrity. A total of 410 Ruthenians and Ukrainians fought in the Croatian army, accounting for the largest percentage of the military as compared to other ethnic minorities.

After the Serbo-Croatian war and to this day

Students of the Summer School of Ruthenians and Ukrainians in Croatia, Zagreb, 1997

Opening of a commemorative plaque on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the resettlement of Ukrainians to Croatia, Slavonski Brod, September 2000

The final concert of the Manifestation on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the resettlement of Ukrainians to Croatia, Slavonski Brod, September 2000

Greetings to the participants in the Manifestation “100th Anniversary of Ukrainians in Croatia” from the Ukrainian World Congress

Raisa Trostynska, member of the Department of Ukrainian Language and Literature, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Zagreb. She wrote the textbooks “Croatian-Serbian language. Educational materials” and “Ukrainian – Croatian: phonological, morphophonological and morphological problems”

Raisa Trostynska, member of the Department of Ukrainian Language and Literature, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Zagreb. She wrote the textbooks “Croatian-Serbian language. Educational materials” and “Ukrainian – Croatian: phonological, morphophonological and morphological problems”According to official Croatian statistics for the year 2001, 2,337 Ruthenians and 1,977 Ukrainians remained there.

The next wave of migration consisted mainly of people looking for work. In January 2008, the Ukrainian Community in the Republic of Croatia was founded in Slavonski Brod. As of 2021, the organization included 10 societies with a total membership of about 800 plus 150 individual members.

After the beginning of Russian’s full-scale aggression against Ukraine, Croatia sheltered more than 17 thousand Ukrainian refugees. On May 8, 2022, Croatia’s Prime Minister Andrej Plenković visited Kyiv as a sign of solidarity with Ukraine and promised support for President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky. Croatia consistently supports Ukraine on its way to the EU.

Today, Ukrainians in Croatia have their own Central Library of Ruthenians and Ukrainians in Zagreb, Ukrainian departments at Croatian schools and the Department of Ukrainian Language and Literature at the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Zagreb.

UWC is sincerely grateful to honorable Slavko Burda for his help in writing this article.