Analysis: When Russia razed Mariupol to the ground, they decided to stage a variety show in the theatre where they killed over 600 people. Oksana Dovgopolova, curator of the Past / Future / Art memory culture platform and Doctor of Philosophy, explains how Russian culture kills.

by Oksana Dovgopolova

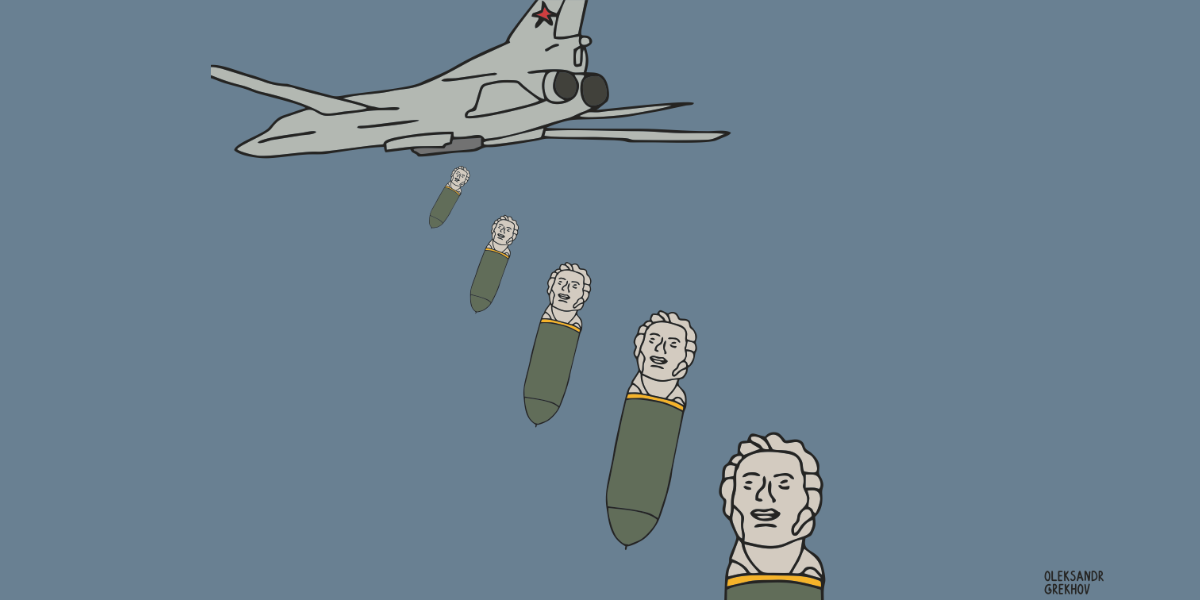

In 2022, the Russian army wiped the Ukrainian city of Mariupol off the face of the earth. They indiscriminately destroyed residential quarters, industrial enterprises, and even a drama theatre. An aerial view of the theatre, with the word CHILDREN written in front of the building in huge block letters, circulated in U.S. and French media. That warning, though, didn’t stop the pilot from activating the launch button and bombing the theatre. He was just following orders, right? That day, over 600 people hiding in the bomb shelter under that theatre met their doom. In fact, the exact number of victims is unknown, as the new “overlords” of Mariupol (or, rather, of the city’s ruins), simply removed the remains, without identifying them, and just moved them to some unknown place. While a criminal’s desire to hide the evidence of their crimes is understandable, the Russian authorities didn’t stop there; instead, they announced their plans to restore that theatre over several months and celebrate it by staging a variety show. As if they are trying to show the whole world that they didn’t destroy the city, looting everything that somehow remained intact, but instead connected the empty city to civilization. The looting, by the way, was on a grand scale: they took some new trolleybuses, and even a fountain, to [the occupied so-called Donetsk People’s Republic] DPR. It’s as if the occupants are trying to send a message: we are not robbing this city, we are taking care of it, as civilized people, and the Drama Theatre will be the first thing up for restoration. Finally, the poor citizens of Mariupol will be able to breathe freely, soaking up the great, enlightened, and world-famous Russian culture.

“Apolitical” Culture

Since February 24, 2022, Ukrainian cultural figures have been actively promoting the demand to Cancel Russia, insisting that Russia uses culture as a weapon. Ukrainians are being assured that people from other countries totally understand their feelings and condemn Russia’s aggression, but that culture is apolitical and one shouldn’t bring the war into a sphere that’s supposed to unite people.

Citizens of different countries have been told for many years that there are two Russias: one is Putin’s Russia, and the other is the Russia of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, Tchaikovsky and Pushkin. Allegedly, the second one is “more real.” Not everyone is so lucky to simultaneously have two versions of their country that manage to not intersect in space. So, you don’t like Putin’s Russia? Feel free to “emigrate” to the Russia of Tolstoy, or Dostoyevsky… or, perhaps, Tchaikovsky — whichever is best suited to your tastes. We, on the other hand, only have one Ukraine. And we have to somehow deal with the two Russias (although having to deal with even one is too much already). In fact, people in Ukraine know that there’s only one Russia, incorporating both Putin and Pushkin (of course, the latter has no responsibility for the rise of the first). So why is Ukraine right to demand a boycott of Russian culture?

Culture is something that defines the state’s place in the conventional hierarchy of world leadership.

It’s binding for a culture’s self-presentation to have its cultural product represented in world museums and theatres, shaping the cultural canon. Creating great museums/theatres and being accepted in world museums/theatres means having one’s place in high culture, a place at the world’s round table. Not everyone is allowed here because not everyone lives up to the standard. This has nothing to do with politics, right? Wrong, it has everything to do with politics. Because culture can be deprived of its voice. And it’s not just the lack of representation in, say, the exposition of the Louvre that’s at stake: when a certain culture’s voice is muted in the choir of the world’s voices, it becomes easier for others to believe that that culture, that people, that country don’t exist. When, on the contrary, some culture can appropriate another culture’s advancements and claim them as its own, it becomes easier for the rest of the world to justify theft, war, and aggression. When they just don’t hear the other culture’s voice, it’s easier, instead of condemning aggression unconditionally, to hesitate and theorize that “things aren’t that clear-cut.”

That is exactly what Ukraine had to deal with for many years. Ukraine’s voice wasn’t heard because of Russia’s loud voice that insisted that there is no such country as Ukraine, Ukrainians are the same as Russians, and those who refuse to recognize the Russians as their closest related people are enemies to common happiness and their own people, as well as aggressive nationalists. One can’t but admit that the world has been listening to Russia for many, many years. Why? Because there’s the great Russian culture, there are Russian composers and Russian ballet, Russian avant-garde and Russian cultivated collectors who created wonderful museums in St. Petersburg and Moscow; there are references to the “Russian Seasons” in Paris, there are the Faberge eggs “and so on.”

Shadow History

Russian culture is very generous and friendly, and eager to support any talented Ukrainian. After all, it was the Russian artists who bought Taras Shevchenko out of slavery — so, knowing that, who in their sound mind would dare to accuse the Russians of repressing the Ukrainians or of some mythical colonial policy? Besides, it’s quite easy to find “sincere admirers” of Ukrainian culture [among Russians], who will eagerly tell you about how they admire [Ukrainian] folk songs, voices, dances, and the beauty of Ukrainian women. They will be consistent in both their admiration and their inability to grasp why it’s perceived as condescending. We didn’t deprive anyone of their voice, on the contrary, we helped them be heard!

Indeed, Ukrainian cultural figures are present, either on the map of Russian culture or on Russia’s ethnographic map. A historian from South Africa once shared a similar problem with me: South Africa is often represented in the European museums of ethnography, but never in the history museums. Why is that?

The great philosopher Hegel once introduced the concept of “historical” and “non-historical” peoples. A non-historical people is not a subject of history, it is simply inscribed in the orbit of activities of other nations. A non-historical people would not have their state, therefore, the state is the path of God in the world. One could consider Hegel’s theory as outdated, yet its shadow looms over certain parts of the world. The people of Ukraine, along with the Central or East European region, find themselves in such a shadow. As the American historian Mark von Hagen notes in his article with the self-explanatory title “Does Ukraine Have a History?“, for a long period this territory just didn’t exist on world maps, lost within the Romanov and Habsburg empires, and later within the German Reich and the USSR. There were some marginal empires that the rest of the world perceived as “something bordering with Russia.”

History is a rather conservative discipline. Ukraine remains in the shadows of imperial histories: one can easily find a Center of Russian Studies at American and European universities but has to look hard for a Center of Ukrainian Studies. Indeed, such centers can only be found at the University of Alberta in Edmonton (Canada) and Harvard University in the USA. Despite Ukraine being the focus of international attention several times in the 21st century (the Orange Revolution of 2004, the Revolution of Dignity and occupation of parts of Ukraine in 2014, and the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022), that didn’t contribute to radical change in viewpoint. As paradoxical as it may sound, even in the context of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, the world media turned for an expert assessment of the situation to either experts on Russia or experts from Russia, seeing nothing wrong with doing so.

Okay, fine, readers might say, we got it that it might be worth developing academic studies, but what does culture have to do with that? Like, Tchaikovsky is not bombing Mariupol, Dostoevsky is not shelling Kyiv — that is true. Yet here’s another true thing: Russia has been using its culture as a weapon and a means of disenfranchising [Ukraine] and justifying expansion for far too long.

Suffocating Brotherly Embrace

For over two centuries, Russia has made every effort to deny the very existence of Ukraine. Already in the “History of the Russian State” by Nikolai Karamzin, the great narrative of the Russian State is created, saying that that State originated in Kyivan Rus’, and then, beginning from the 15th century, began the Gathering of the Lands — exclusively their own lands, of course, saving them from foreign influences. According to Karamzin, a single nation naturally organized into one unified state — they just relocated their capital city. So, where are the Ukrainians, then? They just don’t exist, they are simply part of the Russian people. One willing to prove their existence is a separatist.

So, if Ukrainians indeed never existed as a separate people, why would the Russian Empire need to issue special documents declaring the Ukrainian language and culture a fiction in the first place? Let me remind you of the wording from the Valuev circular of 1863, which proclaimed that at the state level, the “Little Russian” language was a part of the Russian language and didn’t exist separately. Since it was spoken by commoners (and thus couldn’t be a language of high culture), it was declared to be a version of Russian corrupted by Polish influence. The so-called Ukrainian language, the circular asserted, was incomprehensible and artificial, and the “Little Russians” themselves (Sic! The authors of that document found it important that the circular was presented as one representing the needs of native speakers, not as violence on the part of the Empire) consider it an invention by the Poles in order to pursue their separatist aspirations.

When the existence of the Ukrainian people became too awkward to deny after the Ukrainian People’s Republic (1917-1922) was created (and gained international recognition), the successor state of the Russian Empire, the USSR, resorted to another tactic, launching the concept of “friendship of peoples”, according to which there is a centuries-old desire of Ukrainian and Russian peoples to live together. So, the fraternal nations that emerged from a single cradle (Kyivan Rus’) were divided by insidious enemies, but reunited in 1654. Since then, anyone who wants to break the fraternal embrace is recognized as an agent of foreign influence, a traitor, and an enemy of the people’s aspirations.

The USSR’s imperial policy hid exactly behind the surface of that “friendship of peoples.” The extremely bright surge in Ukrainian culture of the 1920s ended with the political repressions, imprisonment, and murders of the artists from the Executed Renaissance, followed by Soviet ideology creating that impenetrable image of brotherly friendship, with the Russian “brother” necessarily being the older one.

The Soviet cultural canon absorbed some elements of Ukrainian culture, for instance, Taras Shevchenko’s poem “Zapovit“ (Ukr. “Testament”) was taught in Soviet schools as part of the national culture. To “neutralize” the centrifugal tendencies of Ukrainian identity, it was important to remove any hint of coercion (namely, any mention of either the Valuev circular or the similar Ems Ukase) and emphasize the sincere support of Ukrainian culture by the Russian state and cultural figures. At the same time, the natural belonging of this or that cultural figure to the field of Russian culture becomes the focal point. Taras Shevchenko was presented as a Russian artist (after all, it was the Russians who bought him out of slavery, and he studied at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts with scholarships). Everything that didn’t fit into belonging to Russian culture was recognized as non-existent. Every anti-Russian statement was reinterpreted as a statement against the tsar regime and the dream of a free existence of fraternal peoples in a united socialist state. Any creation in the national cultures of peoples of the Russian Empire was assumed as something that got its impulse from and owed its very existence to the Russian culture. This is a very important point, allowing us to understand the means of appropriating national cultures [by the Russian culture], as well as the true meaning of some modern Russian practices carried out where Russia is waging war.

Matrix of Imperialism

The Empire proclaims itself the defender and inspirer of cultural development, i.e., “we bring civilization and culture to peoples who didn’t have their own written language, we are the enlighteners.” At the same time, in Uzbekistan, for instance, literature written in Arabic (a centuries-old layer of local culture, poetry, and science) was physically destroyed. Nobody should have any doubt that the Empire always acted in the best interest of peoples inhabiting it. Every subject of the Empire who managed to create something was appropriated and recognized as the exclusive property of Russian culture, no matter how they identified themselves. If you were impossible to fit into the Russian narrative, you never existed. That is why the philosopher Hryhoriy Skovoroda was branded as Russian, but at the same time the Empire boosted the image of a self-educated traveling philosopher, despite the fact that his “travel destinations” weren’t limited to the Slobozhanshchyna region; he went to Europe, got a European education of the highest quality, and mastered several European languages. So why was presenting Skovoroda as a self-educated philosopher so important for Russia? Because that way it was easier to integrate him into the Russian narrative, with the context of the European Baroque and the influence of Western thinkers left out completely.

When Russia wants to mark its presence somewhere, it certainly does it through culture.

That ought to create an attractive image: look, this country is not about violence, it’s about culture and modernization. Russia uses monuments to Pushkin and Russian Cultural Centers to mark its influence zones. When anyone is uncomfortable with it, they are branded as a savage or a “primal” nationalist. Like, who can be unhappy about a monument to a poet? In 2009, for instance, a monument to Pushkin became an urgent necessity in Eritrea. With Pushkin monuments as markers of Russia’s influence zones, no wonder that this East African state is one of Russia’s few allies in 2022, faithfully voting in the UN for the decisions needed by the empire.

Culture is a legitimate space for one nation to be present on another nation’s territory. Who would see a threat in, say, the British Council or Alliance Française? Who would distrust the activities of the Rossotrudnichestvo (with its full title being “Federal Agency for Affairs of the Commonwealth of Independent States, Compatriots Residing Abroad and International Humanitarian Co-Operation”)?

However, unlike the British Council and Alliance Française, Rossotrudnichestvo is not only a body that represents Russian culture abroad. It is also a channel for attracting those who are designated as compatriots abroad and signing them up for the Russian agenda. This is what the concept of the “Russian World” is based on:

explaining to Russians that Russia has a claim on something in other states;

explaining to Russian speakers in other states that Russia cares more about them than their own states.

All that provides a basis for justifying Russia’s aggression against other states, as the Russian people are seasoned by years of propaganda into thinking that some of “our people” are living in a hostile environment; that there is some “normal” coexistence of fraternal nations interrupted by some newly emerged “Nazis.” The latter works like magic for both the domestic Russian audiences and assumed “European” ones, as, after WWII, any movement with a pronounced national idea is perceived with caution as potentially Nazi. Let me remind you once again of Mark von Hagen’s reasoning: Ukrainian culture has fallen into the field of “bad nationalism”, which Europeans are suspicious of.

The Borders of God(li/less)ness

The world genuinely believes in some special Russian spirituality, their special way, their understanding of something real. The Russians also genuinely believe in their own godliness, and this belief translates into their confidence in their right to expand their territory and dictate their will to other states. In Russian schools, they teach wonderful love lyrics by Fyodor Tyutchev. The textbooks, however, fail to mention his poem “Russian Geography.” Let me cite the original text for you:

Москва и Град Петров, и Константинов Град —

Вот царства Русского заветные Столицы…

Но где предел ему? и где его границы —

На север, на восток, на юг и на закат?

Грядущим временам судьбы их обличат…Семь внутренних морей и семь великих рек…

От Нила до Невы, от Эльбы до Китая,

От Волги по Евфрат, от Ганга до Дуная…

Вот царство Русское… и не прейдет вовек,

Как то провидел Дух и Даниил предрек

Moscow, along with the cities of Peter, Constantine,

Are the covenant capitals of the Russian realm.

But where its borders lie under its ruler’s palm?

In North and East, in South and West — the time

Will soon reveal just what their fate defines.

With seven inner seas and seven mighty rivers,

The Volga and the Nile, and all the way to China,

The Elbe, the Neva, Danube, Gangue, Euphrates,

That is the Russian Kingdom, the one that never quivers,

Just as the Holy Spirit and Daniel prefigured.

Tyutchev was a Russian diplomat, who spent many years in Germany and knew European culture well. He was a truly talented poet, capable of conveying the subtlest shades of the feeling of love. He wasn’t some lord of a manor from the Russian hinterland who, out of boredom, painted imaginary pictures of world greatness; rather, he was someone whom Russians themselves considered a European. Don’t you find the lines of the “Russian Geography” disturbing? Living in the 19th century, the poet saw the concept of Moscow being the Third Rome as a comprehensible reality. “The two Romes have fallen, the third stands, and there will be no fourth!”, Philotheus, a 16th century monk from Pskov, boastfully proclaimed, explaining the concept of transforming the Eternal Empire, which first manifested itself in the Roman Empire, then in Byzantium, and then in its “heir”, Russia. Interpreting the verses of the Old Testament, Philotheus described Rome (the Eternal Rome, in all three of its incarnations) as a force opposing the advent of the Antichrist. Thus, Russia is not just a Great state — it’s the world’s most important state, working against the Antichrist. While every other country is unable to raise their head, Russia is the one standing guard for the rest of the world. This gives Russia the right to use violence, as this is for the common good.

By looking at Tyutchev, we clearly understand that there aren’t “two Russias”, with one of them violent and the other one shining its culture (though it usually means that, for the sake of that shining culture, one could turn a blind eye to certain “mistakes”). It’s the same mind that creates both the most tender love lyrics and the apocalyptic pictures of the Russian State’s global domination. They are two sides of the same coin, organically completing one another.

In modern culture, the figure of the poet Pushkin is represented in the context of glorifying love and male friendship, of the freedom-loving pursuit of a happy and free Russia of the future. But what about the ominous verses of his poem “To the Slanderers of Russia” (Rus: Клеветникам России, romanized: “Klevetnikam Rossii”), oozing with vile contempt for Europeans (in this case, for French politicians who condemned Russia’s suppression of the 1830 Polish uprising), alleging that they impotently hate what they cannot understand. “What moves your idle rage? Is’t Poland’s fallen pride?”, asks the poet and adds, clearly irritated: “‘T is but Slavonic kin among themselves contending, An ancient household strife, oft judged but still unending, A question which, be sure, you never can decide.”

Sounds similar to Putin’s disgusting statement that there is no such country as Ukraine, doesn’t it? One clearly can’t speak of Poland in a similar tone any longer, nor can one say that about Lithuania. It has since become clear to anyone that there was nothing “household strife”-ish about Russia’s claims on neighboring countries. But when it comes to Ukraine, some Europeans still find it possible to say “it’s not that clear-cut.” War, attacks, and murders are pretty much clear-cut, ladies and gentlemen.

A Landscape Painted with Pain

Why recall the random verses some poet said in the early 19th century, you might ask. This is the 21st century, the world has changed, and so has Russia. Indeed, the world has changed. As for Russia… In June 2022, Mikhail Piotrovsky, the director of Russia’s most famous museum, the Hermitage, spoke about the modern tasks of Russian culture in his interview: “Our recent exhibitions abroad are a powerful cultural offensive. A kind of ‘special operation’, if you like. But we are advancing. And no one can be allowed to stop this offensive.” Thus, the Hermitage director considers his work as another dimension of the so-called “special operation” in Ukraine; he feels like he’s at war (let’s put the euphemisms behind, Russia is waging a war against Ukraine).

Mr. Piotrovsky believes that his country is currently undergoing major global transformations and that every person in Russia has a special sense of historical dignity, which lies in the desire to meet the mission of their country. Being art and part of “our country currently changing the course of history” is of utmost importance, says the director of the Hermitage. Human rights, international law, fulfilling one’s own international obligations? Nope, Mr. Piotrovsky wouldn’t even think about it. What are those, compared to the Great Mission? Protruding from the modern European costume of the chief Russian museum curator is the head of a medieval monk, who proclaims the greatness of the Third Rome.

I believe it’s important to mention one more thing, one that’s very unpleasant for the evangelists of the concept of “the two Russias.” Usually, the slightest mention of “Slanderers of Russia” or something like Mr. Piotrovsky’s pathetic philippics (he is not the first and not the only one in this series) is accompanied by indignant comments from lovers of Russian culture: “You don’t know Pushkin well enough; he hated the unjust government, he was friends with the Decembrists! Isn’t it clear that he was forced to write about slanderers because he was dependent on the Tsar?” Or, “You have to understand the director of the museum (theatre / university / gallery — please underline as necessary), he is in charge of hundreds of employees and can’t just put them all in the line of fire!” Well, here’s some bad news for those who tend to “understand” everyone. Yes, maybe Pushkin was indeed a wonderful person suffering from being pressed into writing something he was expected to by the authorities. But his suffering is simply a fact of his private biography. I can even sincerely sympathize with him. But overall, his inner attitude towards the state is irrelevant, the important thing is that the Empire took advantage of his writing. It was used as a weapon, as a cultural marker to stake out the space. In an Empire, one is deprived of having human dignity, the only dignity available is that same “historical dignity” that measures the extent to which a person a part of the “historical mission.”

Russia sincerely believes that its mission is to carry out global transformation. They truly believe that they are the ones bringing culture to the unfortunate “savages.” When the Russian army was razing Syrian cities to the ground, the Russian state told the world how Russian specialists were going to restore Palmyra (who cares that there are no such specialists in Russia?) — and organized theatrical events there. When Russia razed Mariupol to the ground, they decided to stage a variety show in the theatre where they killed over 600 people.

During that same period, they filmed a music video where artists wrapped in the Russian tricolor sang on the ruins of Mariupol about their feelings, using some random (sometimes non-existent) Ukrainian (Ukrainian-sounding) words, and for some reason, the lyrics depicted some duck swimming somewhere and mentioned that the Russians will keep the Ukrainian language to themselves as a trophy.

It was a parody of the Ukrainian folk song “Plyne Kacha”, with some Russian words inserted into it. Hardly anyone (except for Ukrainians) can truly understand the level of bullying intended here.

Continue reading this article at The Heinrich Boll Foundation website