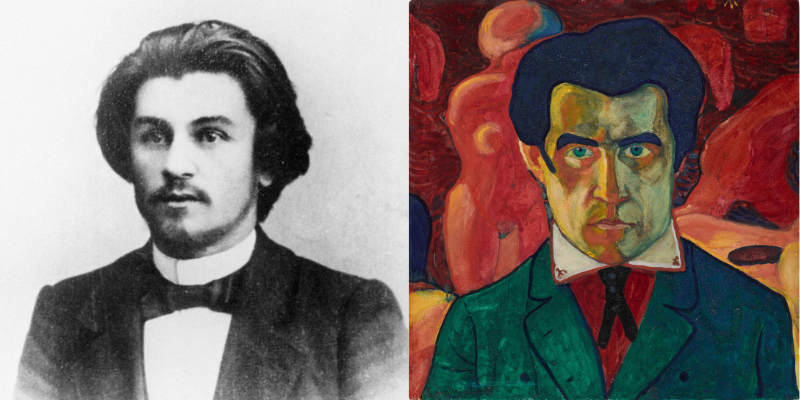

On February 23, 1879, Kazimir Malevich, the world-famous avant-garde artist and the creator of Suprematism, and one of the founders of Cubofuturism, was born.

Malevich was born in Kyiv in a Ukrainian-Polish Catholic family. His father was a sugar production engineer, so the family often moved from one Ukrainian town to another, from sugar factory to sugar factory – Podillia, Kharkiv, and Chernihiv regions.

As a teenager, he became interested in drawing in Konotop, Sumy region, and then studied with the outstanding Ukrainian painter Mykola Pymonenko at the Kyiv Art School (1895-1897).

Between 1904 and 1927, he improved his skills, painted, and taught in Russia and Belarus. He became one of the founders of abstract art. In December 1915, Malevich first exhibited the painting “Black Square on a White Background,” which became an icon of abstract art.

In 1927, Malevich returned to Kyiv, Ukraine, where he first experienced a favorable environment for creativity. Until 1930, he taught at the Kyiv Art Institute, but repressions against the Ukrainian intelligentsia forced the artist to move to Russia again – to Leningrad.

Although Malevich spent much of his life outside of Ukraine, he never severed ties with it. During the interrogation in the fall of 1930 in Leningrad, he called himself Ukrainian. He was accused of spying for Poland and threatened with execution, but in the end, he served “only” three months in prison.

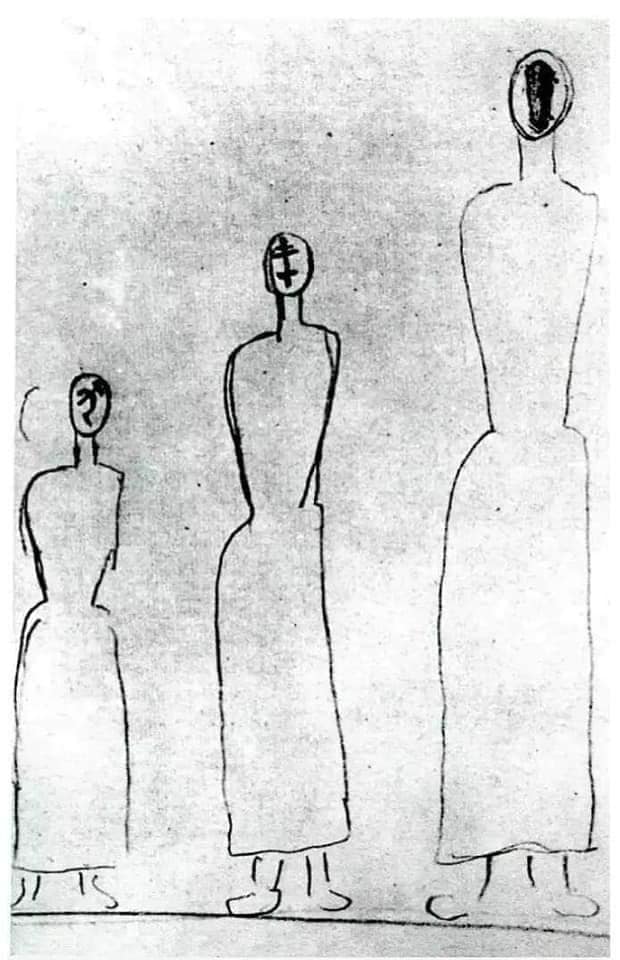

Malevich was one of the Ukrainian artists who depicted the Holodomor of 1932-1933 in Ukraine, writes Diaspora.ua. His pencil drawing, known as “Where there is a hammer and sickle, there is death and hunger” (words from a folk song popular in the 1920s and 30s), depicts three figures whose faces have been replaced by a hammer and sickle, a cross and a coffin.

Many of Malevich’s “peasant” paintings of the 1930s contain hidden, symbolic messages of protest, such as the absence of faces.

“Malevich was the only artist who showed the tragic situation of the Ukrainian peasants during the criminal forced collectivization,” claimed the French art historian and author of several monographs on Malevich, Jean-Claude Marcadé.

Kazimir Malevich died on May 15, 1935, abroad, in Leningrad.

Despite being Ukrainian by origin, artworks and even openly expressed self-identification, many sources still call Malevich a “Russian and Soviet” artist. Such a fate befell many “known unknown” Ukrainians – artists, scientists, and politicians. Yet, the truth cannot be stopped – despite all the efforts of Russian propaganda. Recently, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, one of the largest museums in the world, has made changes to its website, recognizing Arkhyp Kuindzhi, Illia Repin and Ivan Aivazovsky as Ukrainian artists.